Back in May, I wrote a post called “Being a Young Female Lecturer; Or, Why Age and Gender Still Matter.” It generated an awful lot of interest given the very specialized nature of my blog. I think this was partly because it was cranky – you seem to like it when I’m cranky – but there also seems to be a genuine interest out there in how we continue to navigate gender stereotypes, despite it being 2013. Alas, this post won’t be quite as cranky, but it will continue to take on the really troubling gender-related issues I find myself coming up against, again and again, as a female intellectual.

First of all, as I confessed back in May, I have a tendency to do things “like a man.” As one reader cautioned, however, this may perpetuate some of the inequalities that women still experience at the university and beyond. I’m not going to lie; my first reaction to this was of the “oh, f@%! off” variety. In fact, part of me still feels that way and is incredibly defensive of my right to possess a somewhat masculine demeanor. This part of me will continue to fight for a space where being a woman isn’t defined by any particular character traits and where I can be an equally good person without having to worry about doing so in either a masculine or a feminine way, whatever the hell that means anyway. I want to create my own identity, fortified by categories of my own choosing. And I don’t really care if that offends people.

[Guilty!]

But the more reasonable part of me takes the point. Some of my behavior has, without question, been detrimental to those around me. I thought until recently that I had tamed the uglier side: the competitive streak, the unbridled volume and assertiveness, the desire to always speak when I have an answer instead of leaving room for others, etc… And these traits are, for the most part, now under control. What I was still doing, though, was privileging a particular mode of behavior that is often associated with men. I was doing this explicitly, and I was doing it in the classroom. Sadly, I only noticed this tendency when leading a seminar full of unusually bright students. The group was divided almost equally between men and women, and each and every student had what it took to hold their own. And yet, with the exception of 2 or 3 ladies, the women preferred not to engage with the group as a whole. Since they were all very adept, especially when broken down into small groups, my response was to encourage the women to “be more confident.”

[Speak up ladies!]

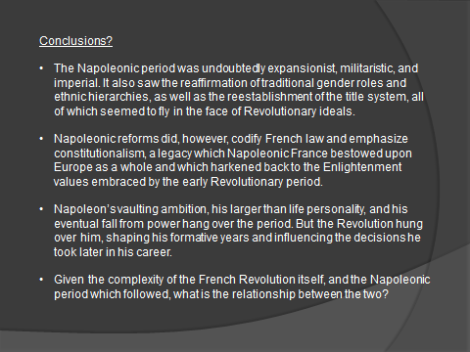

Put another way, the feminist in me initially reacted by bemoaning the way that North American culture socializes women not to claim public space, to avoid confrontation (or risk being ostracized as a bitch), and generally to be respectful of the opinions and ideas of others while not giving enough thought to their own innate self-worth. I therefore told these women that they should claim their space and find their voice. And that is true… to an extent. But what’s also true is that the way our society socializes men – to assume that all space is their space, to constantly compete and assert oneself, and to possess the kind of confidence that can come at the expense of empathy – is not always the right way to go either. A lot of the things that bother me about the universities (and society more generally), come out of this allegedly masculine culture, and I acknowledge that there is value in a quieter form of continual compromise. As the weeks passed, I thus began to question my assumptions, and instead of telling the women to be more assertive, I started asking the men to make more room for other approaches. I began to suspect that what we need is more balance, and to stop dismissing different ways of living and communicating just because they’re not as loud or as attention-grabbing.

I was thinking about these issues as I read a blog about the online abuse suffered by publicly engaged female intellectuals. The author of the blog described the increasing institutional pressure for intellectuals to move beyond the hallowed halls and to engage the world around them. This is something I take very seriously, especially in recent years, as I have started to react more strongly to the now-pervasive rhetoric about how humanities degrees are allegedly “useless.” A very real anger over the short-sightedness of this position has pressed me to lead by example; to stand up and prove that my Liberal Arts training has value. In other words, I now strive to be a public intellectual, if in a somewhat limited capacity. My role as a teacher is part of this, but I also write open-access Facebook “notes,” maintain this blog, and engage actively with politics – I even ended up in a constitutional debate with the former Minister of Finance during the student protests in Quebec in 2012. I’ve also become interested in things like “Informed Opinions” (a group which encourages female intellectuals to take on the role of “experts” by writing articles and op-eds for the mainstream media), and am now fully engrossed in feminist debates that I used to ignore.

And yet, I cannot help but think about that seminar. Particularly after reading a blog post that detailed the disturbing online responses to female intellectuals who take on a public role. We all know that the mainstream media is only interested in what Hilary Clinton is wearing and who does her hair. Many of us also know about Anita Sarkeesian, and the online attacks that targeted her because she dared to criticize the sexist nature of video games. But a lot of us don’t realize that even more minor figures – lesser known female professors who enter the Twitterverse, for example – are similarly harassed. All of this is driven by the “wild west” nature of the internet, which is buttressed by the lack of person ties and the potential for anonymity that exist online. Here, a culture of bullying is not just allowed; it is encouraged. And it often has an overtly anti-feminist edge.

This is where we want women to speak up. This is where universities want them to claim their space and let their voices be heard. And this is where I entered the fray, equipped with all the same tools as the men with whom I do battle in this banal and inglorious war. But I ask you this: is being more like me – unapologetically aggressive and willing to fight fire with fire – really going to fix everything that’s wrong with the scenario I just described? I’m not convinced.

[Perhaps more sage advice]

Several weeks ago I confessed on Twitter that I no longer let men sprawl into my space on the bus. I feel entitled to my seat and the space that surrounds it, and whatever unconscious stone-age logic that encourages men to sprawl in order to assert their dominance can be damned! But I also asked the Twitterverse if perhaps this wasn’t empowerment – perhaps, it was just equally bad behavior. I’m still not sure, and I’m still not sure how to defend myself without becoming part of the problem. I’m genuinely confused as to whether telling people to stand firm and speak up – during either physical battles for space or virtual wars over the signifiers of online authority – is the right approach. Undeniably, someone has to draw a line in the sand and say “enough is enough,” and this is a very assertive act. But, increasingly, I suspect that society needs to stop telling people to speak up all the time, and instead start telling everyone to learn when to shut up and listen.

My Previous Thoughts on Gender:

The Informed Opinions Site:

http://www.informedopinions.org/

“Take Back the Net” blog post: