This week, the Lianne McTavish and I swapped posts! She writes the Feminist Figure Girl blog and if you haven’t seen it before, go read it right now! It’s epic and is, without question, my favourite blog. Lianne is a 45-year-old female professor, who decided to combine her identities (scholar/gym rat) in 2010 to create Feminist Figure Girl, a bodybuilding honey badger. She started her blog blog when she was training and dieting for her first figure competition, held in June of 2011 and has now written a book inspired by the process. Her blog is filled with feminist reflections on food, working out, sexuality, and bodies, and I heartily encourage all my readers to check it out! Here, Lianne takes on teaching. In many ways my mirror, she explains what useful lessons can be pilfered from the classroom and used in the presentation of one’s research.

[Feminist Figure Girl]

Many professors and teachers are preached the golden rule: teaching and research go hand in hand, mutually informing each other. Yeah right, you might think. So why are we rewarded with less teaching when we win large grants or move up the food chain to become senior scholars? I think you can see the irony. Here I will admit that I am one of the bad guys, actively striving to spend less time in the classroom as I gain authority/seniority. In fact, in my dream life I would never have to teach again. If you are shocked right now, then you are no friend of mine. For when I close my eyes and click my heels together, I am transported from a classroom filled with twenty-year olds wearing pajama pants into the kitchens of King Henry VIII at Hampton Court. There I work as a food historian, recreating Tudor recipes using open fire pits, large cauldrons, and heavy spits laden with chunks of beast. In another dream, I do research in archives, libraries, museums, and gyms 100% of my time, never again offering an undergraduate course. Now don’t get me wrong; I do not loathe teaching. Far from it. I even think that I am pretty good at it. All the same, course preparation and grading prevent me from doing what I absolutely love and find far more gratifying: writing. Whenever I am not cooking or lifting weights, I am producing academic books, popular articles, catalogue essays about contemporary art, and posts for my blog called feministfiguregirl.com.

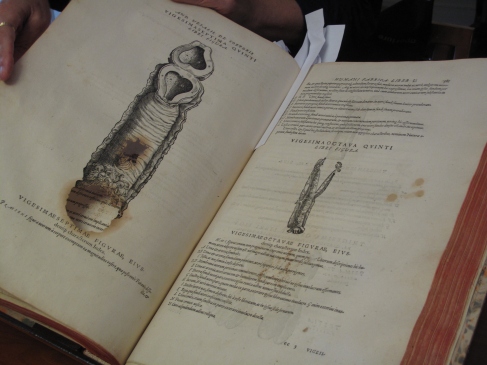

At this moment, I am sitting in a classroom at the Rare Book School, held at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, secretly composing both a chapter of my book and this guest post, while listening to the instructor talk about Doctor Beaumont and his stomach experiments. Cool. I am clearly a big fan of multi-tasking, linking activities together to produce a superior form of knowledge. That is why I am also trying to look more favourably on my 20 years of teaching experience at universities, medical schools, and art galleries. I realize that in addition to learning how to manage large groups and grade efficiently, I have become a better writer by teaching. For the rest of this post I will list some of the writing tips that ultimately stem from the classroom. Please expand on and respond to them in your comments.

[FFG’s current reading material]

1) Be methodical. There is no need to deliver all of your material on a particular subject at once. It works best to start with the basics and then build up toward complexity. Just as you would not overwhelm your students with too much information, so too should you avoid overwhelming your readers. Resist the urge to show off by displaying everything you know and instead focus on the more important goal at hand: communication.

2) Pace yourself. While teaching I regularly pause or create some kind of interlude in order to give my students a rest from taking in new information, to let them catch up on their notes, or simply to allow them to close their eyes for a moment of peace. Do the same for your readers. Unroll your argument at a regular pace that will depend on the topic at hand, being sure to give readers time to reflect and rest along the way.

[Pace yourself]

3) Repeat yourself. Or at least drive the point home by reminding readers why what you are saying is important. Just as your students cannot pay attention for hour after hour even when fueled with Tim Horton’s coffee, nor can your readers concentrate endlessly. Provide them with signposts in the form of subtitles, key terms, or literal reminders of what you have previously argued in order to guide them along the way, something that is particularly necessary in long articles and chapters. In short, be kind to your readers without insulting their intelligence.

4) Be generous. Don’t adopt a defensive or know-it-all tone while writing, just as you should never do so while teaching. In my experience, students will simply stop listening if you become bombastic. Similarly, even the most interested readers will disengage if they decide that you are a pompous ass. By all means be opinionated and self-confident while performing both types of work. Do so, however, in a way that invites rather than forecloses questions. While writing, allow people to take your ideas and use them to pursue their own projects and questions.

5) Follow your passion. This is the advice I give most often to my graduate students. After reading their drafts I will say: “I can tell that you hated writing this section, but that you are in love with the second half of this chapter. So delete all the shit in the first half and expand on that about which you actually care.” If you write out of obligation rather than genuine interest, the results will most likely be laboured and unpleasant to read. I learned this rule during my first job teaching a 3-3 course load that required me to develop new courses every single year. As I worked my way through about 21 new course preps—and yes I did manage to publish at the same time though I did not do too much partying—I realized that I was a terrible teacher when I was uninterested in the content. When forced to teach a survey course on Canadian art, something I had never studied, I lightly skipped over the eighteenth-century landscapes that I considered boring and focused on modern and especially contemporary Aboriginal art, which I found fascinating. Moving quickly to a subject that I cared about was the right decision. Hopefully you are in a position to choose what to teach or at least how to teach it. You almost certainly have this freedom with your writing, so (to repeat) do not write about something that bores the living crap out of you. Your readers will be able to tell.

[Write what you love or face the consequences]

6) Work organically. With this elusive advice I essentially mean that you should not write in separate sections. Just as you teach with the big picture in mind, reminding students of key themes along the way while weaving back and forth in time, so too should your writing unfold within a larger framework. Do not write in a piecemeal fashion, for instance by producing a historiography section, followed by one about syphilis, and then one on tuberculosis. [Can you tell that I am an historian of medicine and the body?]. I have heard that some people will actually write up such sections in random order, using written or typed notes, and then paste them together in a quilt-like fashion. If you write this way, I want you to stop it right now. Yes your work will still get published if you are a “chunk” writer, especially if you are in a non-writerly field, but it will never be as good as something that unfolds in a more organic way by building seamlessly from beginning to end. I am clearly biased, for this is how I write, without using notes of any kind, and always with an expansive goal in mind but without a rigid plan. I attend carefully to style, sound, and pace, as well as to content. I believe that this method of writing requires self-confidence and mastery; it requires you to “own” your material and make it work for you, not the other way around (ie you are not a slave to sources or simply intent on delivering information). I might be a giant weirdo, but I write entire books in my head, without ever taking notes from the hundreds of sources I read, re-finding and then adding quotations, factual details, and notes as a final stage. By the way, these books are both archival and scholarly; they are not just opinionated musings. Perhaps you are thinking: “Professor McTavish, you are completely nuts,” and you are no doubt correct. But give it a try. You might find that this free-wheeling method allows your voice to come forward with strength, while increasing your ease of writing. In the meantime, I will be taking great joy from my own creative process, while doing about a hundred other things.